It may be true that I have been singing in my head, “A blessing on your head, mazel tov, mazel tov,” for a couple of weeks now. But that is another story.

“All these blessings shall come upon you and take effect, if you will but heed the word of your God יהוה:

בָּר֥וּךְ אַתָּ֖ה בָּעִ֑יר וּבָר֥וּךְ אַתָּ֖ה בַּשָּׂדֶֽה׃

Blessed shall you be in the city and blessed shall you be in the country.

בָּר֧וּךְ פְּרִֽי־בִטְנְךָ֛ וּפְרִ֥י אַדְמָתְךָ֖ וּפְרִ֣י בְהֶמְתֶּ֑ךָ שְׁגַ֥ר אֲלָפֶ֖יךָ וְעַשְׁתְּר֥וֹת צֹאנֶֽךָ׃

Blessed shall be your issue from the womb, your produce from the soil, and the offspring of your cattle, the calving of your herd and the lambing of your flock.

בָּר֥וּךְ טַנְאֲךָ֖ וּמִשְׁאַרְתֶּֽךָ׃

Blessed shall be your basket and your kneading bowl.

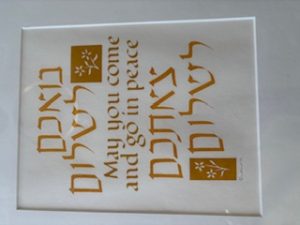

בָּר֥וּךְ אַתָּ֖ה בְּבֹאֶ֑ךָ וּבָר֥וּךְ אַתָּ֖ה בְּצֵאתֶֽךָ׃

Blessed shall you be in your comings and blessed shall you be in your goings.”

(Deuteronomy 28: 3 –6)

Sounds good, no? We talked briefly about them. And how it leads to the Haskivenu Prayer for Peace that includes, a prayer to “guard our comings and our goings.”

This is a shorter list than the list of curses, which we read very quickly and quietly. Do they still apply to us? What if we don’t feel blessed? What if we feel cursed? Where is the hope? Why bother?

Our haftarah takes the longer view. Isaiah teaches this morning:

For in anger I struck you down,

But in favor I take you back.

Yes, it seems that G-d like many of us, and Moses, might be described as having an anger management issue. A little anthropomorphic but it began all the way back in Genesis.

Yet, the haftarah’s message does feel like one of consolation and comfort as we continue to draw closer to the High Holy Days. “In favor I take you back.”

Last week’s haftarah had a similar message:

“For a little while I forsook you,

But with vast love I will bring you back.”

It is like the song we sing from Lamentations at the end of the Torah service and repeat over and over again as part of our selichot High Holy Day liturgy:

hashivenu hashivenu adonai, elecha,

ve-na-shuva venashuva—

chadesh, chadesh yameinu kekedem

Return us, God, to you

and we will return;

renew our days as of old.

We have a covenant with G-d, a brit If you do this, I will do that. We have a series of commandments, mitzvot, laws if you will, given to establish a civil society. A just society, one we want to live in.

This past week has been very difficult. 6 Israelis killed at a bus stop. The 24th yahrzeit of 9/11. The killing of an immigrant by an ICE agent. And yes, the murder of Charlie Kirk. We have to acknowledge them all as horrendous acts of violence. All over the world, there is violence. In our city streets. In Ukraine. In Israel. The list goes on and on. Violence has no place in the world we want to create.

Yet, our haftarah teaches,

The cry “Violence!”

Shall no more be heard in your land, (Isaiah 60:18)

That promise as part of the covenant gives me hope. It won’t however, happen in a vacuum. We have to work for it. Psalms teaches us “Seek peace and pursue it.”

Rabbi Amy Eillberg, the first woman Conservative Movement rabbi teaches, “The Rabbis ask why the verse employs two verbs (“seek” and “pursue”) when one would have sufficed. Their answer: “Seek it in your place and pursue it in other places.” The two verbs, they suggest, convey different elements of the command: seek peace when conflict comes to your doorstep, but do not stop there. You must energetically pursue opportunities to practice peace, near and far, for it is the work of God.”

How do we get to this point:

Rabbi Menachem Creditor reminds us “Pirkei Avot (3:2): “Pray for the welfare of the government, for without awe of it, people would swallow each other alive.” Even when we disagree—especially when we disagree—violence must never be our language. Argue, protest, shout if you must; but do not harm. Din and rachamim—judgment and compassion—need each other. A world of law without mercy would be unlivable; a world of love without any boundaries would dissolve. Law for the sake of love. That must be our path.”

Music helps us when words cannot. Rabbi Creditor listened to Bruce Springsteen’s “The Rising.” Some may have listened to the Broadway musical “Come From Away.” I listened to “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” and “Carry on, Sweet Survivor.” Rabbi Creditor wrote a song soon after 9/11 for his children—really, as he said, “for all of our inner children too”:

Olam Chesed Yibaneh (Ps. 89:3)

I will build this world from love,

… and you must build this world from love.

And if we build this world from love—

then God will build this world from love.

He wants us to, “When the singing ends, let the song move your feet and your hands. Hold the door for someone. Call the friend you’ve been meaning to check on. Teach a child. Volunteer. Advocate for laws that protect life and dignity. Strengthen institutions that serve the common good. Make kindness durable—institutionalize compassion—so that love doesn’t evaporate when the chorus fades.” That’s what Loving our neighbor as ourselves means. That’s what we do.

Perhaps the rabbis of the Talmud had it correct. We should say 100 blessings a day. Saying these blessings creates, as they say these days, an attitude of gratitude.

An attitude of gratitude is the conscious choice and regular habit of acknowledging and appreciating both the big and small positive aspects of life, even during challenges. It involves shifting focus from negativity to the positive, leading to increased happiness, resilience, and improved relationships, and can be cultivated through practices like journaling, mindfulness, and expressing thanks to others.

And the modern-day positive psychologists like Martin Seligman tell us you can achieve those benefits of increased happiness, resilience and improved relationships with just remembering, even better writing down just three things a day. Try keeping a gratitude journal by your bedside.

I never suggest you do something that I am not willing to do myself.

I try to practice an attitude of gratitude, cultivating blessings or catching them in my own life. It isn’t always easy. Earlier this week when I was coming home late and I was tired, I thought if there isn’t any dinner, we would have to go out. I was so grateful that Simon had been to the grocery store and that a lovely salmon dinner was prepared. I was grateful that we had food, the wherewithal to cook, that it tasted wonderful and the house smelled divine. Those are all blessings. I should have done the same thing Friday night I walked in the house, tripped on the dog dish, noticed that the broccoli for meat meal was about to be cooked in a milk pan (broccoli by itself is parve, neither milk nor meat so it shouldn’t have been a problem) and another milk pot was allegedly dirty. Needless to say, I was tired, hungry, and my toe now hurt. What would have happened if instead I said, “Thank you for starting dinner. I love steak, baked potato and broccoli. I am grateful we have food on the table, and that you enjoy cooking.” Those are all real blessings to be grateful for.

It is not the rabbis of the Talmud, or the positive psycologists or even me who want you to think about your blessings, to cultivate this attitude of gratitude. Weight Watchers realizes it can help with healthy living and weight loss. They suggest an awe walk. Going out in your neighborhood and seeing the beauty in nature. That beauty is a blessing too. What beauty can you spy on your neighborhood walk?

Let’s try it here. What are we blessed with? We did some of them at the beginning of the service. Those in the list of 15 are really about getting ready in the morning. (We brainstormed a list. It included life, family, friends, food, shelter, clothing, the roof at CKI that is not leaking, our neighbors who watch our building, health, doctors, the police department. It wasn’t hard to get to 100 between our list and the list we counted in the service which was 65 before we got to the Torah service.)

Our haftarah ends with this sentence:

“Arise, shine, for your light has dawned;

The Presence of GOD has shone upon you!”

This promise, this blessing gives me hope. Know that each of you is a blessing and your light has dawned.